It’s fairly likely you know a little about Urusei Yatsura if you’re reading this. In fact it’s a good bet you’ve at least heard of it if you have some interest in Japanese popular culture, not least because it stretches across 34 manga volumes, 340 episodes of TV anime, 6 feature-length animated films 12 OVAs and a remake/reboot series. In short, it has been and continues to be a Big Deal (within the context of the anime/manga industry).

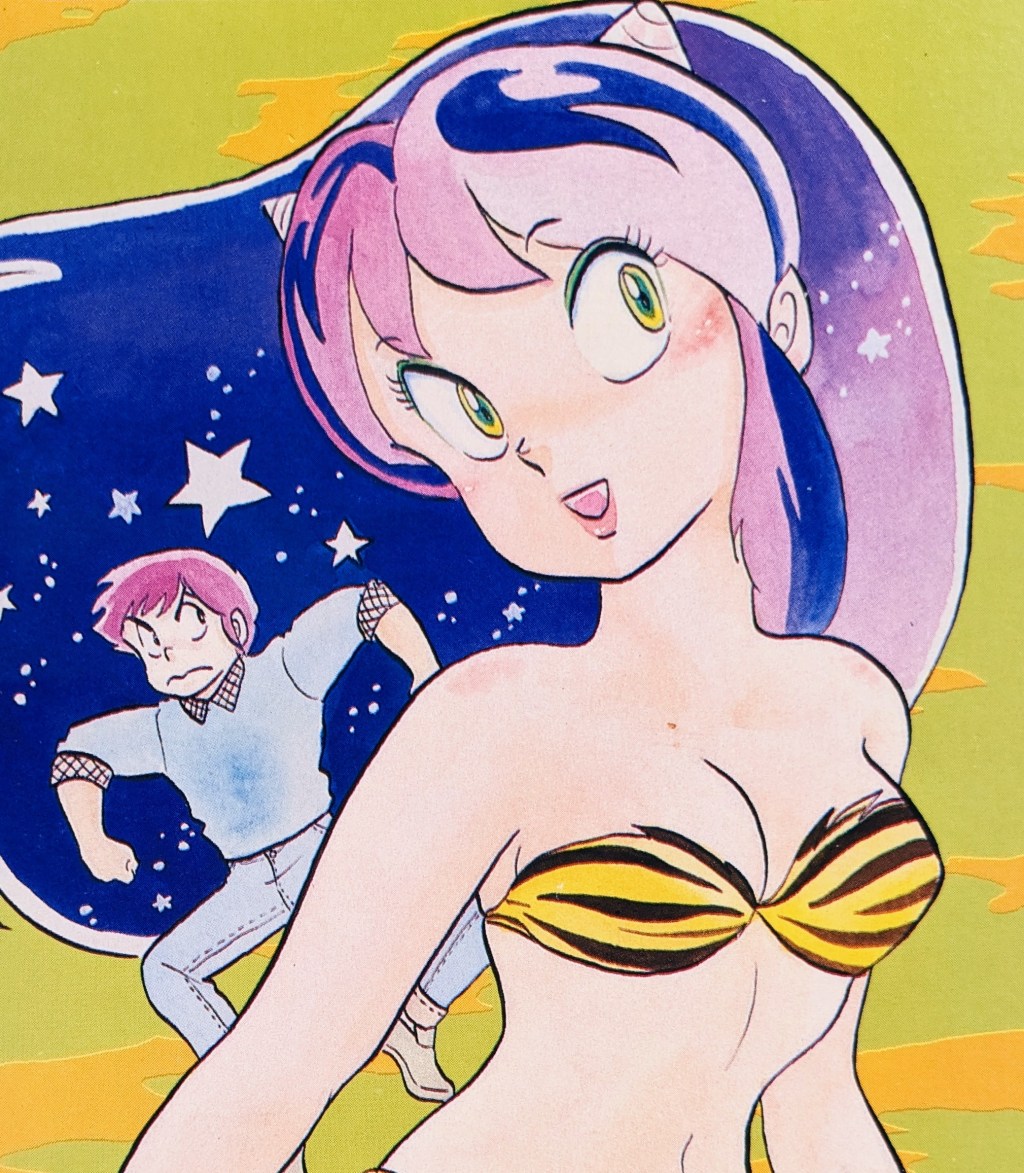

If you aren’t familiar, here is the precis: a disgusting piece of shit lowlife teen is chosen by random to decide if Earth is to be invaded by a race of technologically-advanced horned aliens or not, by way of a game of tag. He’ll have to grasp the horns of an alien opponent over the course of three days. Despite initial doubts, he agrees readily when he realises the opponent will not be the gigantic leader of the aliens, but instead his incredibly beautiful bikini-clad daughter. After two days of complete failure, he wins the game via deeply unethical but ingenious tactics, Earth is saved, and as a result of a bizarre misunderstanding, he becomes engaged to the beautiful alien girl. She stays on Earth with him, and a decades-long history of wacky comedy hijinks begins.

Let us just confirm a few things:

- Lum, the tiger-stripe bikini go-go boot oni dream girl who serves as the tag opponent, was initially intended as a minor character in the life of protagonist Ataru Moroboshi. I suppose it was the intention that the relationship between Ataru and classmate Shinobu Miyake would take centre stage, and Lum’s machinations would serve only as one of the many obstacles that central couple would face. It’s interesting to contemplate a world where Lum never rose to prominence; she has become the anime icon of icons, a character design so successful she demanded a promotion from Ataru’s side piece to everyone’s main girl. We would never have had those really nice Hanshin Tigers commemorative glasses!

- Urusei Yatsura, in both manga and anime form, is a deceptively dense text. I’ve seen people compare it to The Simpsons in that much of the humour in both shows relies on a complex web of satirical and referential humour, the more of which the viewer can comprehend, the deeper their enjoyment of that show (potentially). Being a product of the late 70s, Urusei Yatsura is rooted irrevocably in the late showa era, even in its current “All-Stars” revival, and this is reflected in the attitudes, cultural references, and overall look of the show, down to the supposed namesake for its breakout star, the Hawaiian advertising and bikini model Agnes Lum.

- The title of the show is an inscrutable pun. Put ‘うる星やつら’ into Google translate and it will tell you it means ‘urusei yatsura’. You’ll sometimes see it as Those Annoying Aliens or Those Obnoxious Aliens, but these are compromises: the name of the show is Urusei Yatsura, and that’s all there is to it: there’s no point trying to translate it directly. You’re better off doing as the Italians did and calling it something else entirely (Lamù, la ragazza dello spazio or ‘Lamu the space girl’). The important thing is it’s something about aliens, and the kanji for ‘star’ or ‘planet’ (‘星’) is right there in the middle, hence the many stars that litter the series.

Now, I’d like to talk about the enduring popularity of the series and more precisely the ragazza dello spazio herself, Lum, or Lamu, or Ram, or however you like it. It is always fascinating when a character becomes elevated to a position of almost universal recognition within a culture or across cultures. Obviously from my position as a westerner I immediately think of things like Superman, Scooby Doo, or Darth Vader. As a resident of the UK I might suggest Mr Blobby or Postman Pat. Before the fragmentation of the mass audience makes common reference points between generations and cultural groups a thing of the past, these things enjoyed and to an extent still enjoy the status of what you might call objects of cultural importance: they were of sufficient importance to enough people within a certain timeframe that they were practically universally known to a greater or lesser extent.

Japan, as a result of longstanding practises and resistance to immigration, and in contrast to the USA or the UK, exhibits a far greater degree of homogeneity in terms of its ethnic and cultural makeup than most nations in Western Europe, certainly. What’s more, the very idea of a national culture, of a national people, is more clearly felt and certainly more clearly visible than in most countries. The UK especially seems to be in the throes of a century-long identity crisis in which it is struggling to maintain the impression of a “British”culture while also dismantling the only things we can look to as national achievements that weren’t built directly on the backs of exploited peoples. This piece isn’t about that, so we’ll move on, but it serves to contrast with the apparent devotion to tradition, and to the idea of cultural practise, that the people of Japan display. In such an environment, the ability of “objects of cultural importance” to achieve that near-universality is both enhanced and elongated: once something reaches that zenith, it can take far longer for it to return to cultural oblivion.

Lum was/is one of the elite group of characters that has grown beyond the usual slew of merchandising efforts (though the list of Urusei Yatsura-related products is formidable) and out of the sometimes-insular manga bubble, into popular consciousness. She is present at the Oizumi Anime Gate, a string of life-size statues portraying anime luminaries. There are four statues; Lum, Maetel and Tetsuro from Galaxy Express 999, Joe from Ashita no Joe, and Astro Boy. Clearly, this is rarefied company, the absolute tippy-top of manga’s Mt. Olympus. She has a place among the gods, though she is technically an oni.

a little bit about tropes

Look, we all know about tropes. If you’ve every written anything, and I mean anything, it will probably conform to one or another trope. I’ve heard people say that tvtropes.org and its ilk have ruined their own writing because all they can think of is how whatever they’re writing inevitably falls into a trope. I’ve never felt that way, because it has seemed natural that, should a human decide to express an idea on a page or canvas or whatever you want, it is very likely that idea has some common ground with another idea another human has expressed at some point. What’s more, this common ground, tropeland, is fundamental to an audience’s enjoyment of media in most instances, and never more so than in anime and manga. You know the sort of thing I mean; beach episodes, tsundere characters, magical girls, unusual hair colour, an unending obsession with youth and high school in particular, etc, etc. These are the things that can make you fall in love with the medium, and equally make some bounce off it completely. Manga and anime exist in their own bubble, with their own language that is incredibly difficult to replicate when taken out of its country of origin

Everything is subject to tropes, of course, and if you feel the need, you can take any particular piece of media and break it down semi-scientifically into its constituent parts, though doing so may prevent you from truly enjoying anything again. Let’s not go too far down the rabbit hole here but Urusei Yatsura is no exception: there are tropes in abundance, and the series as a whole probably originated a few. It would be hard to argue against Lum’s status as a ‘magical girlfriend’, though her magic is more on the alien high-technology side and she’s really more Ataru’s fiancé than simply girlfriend, despite his initial feelings. It’s also, in a way, sort of, a harem story, in that Ataru would like it to be; there are a host of beautiful women in his life, he considers them all fair game, but only one every seriously considers him as a partner. Of course, due to the unstable and chaotic world in which Urusei Yatsura takes place, none of these things are treated with anything approaching seriousness. Even the central relationship is given only fleeting moments of development, forcing fans to pick over the scattered bones of one or two scenes where Ataru and Lum might come close to confronting the nature of their coupling. Though the series has passed from the pen of Takahashi herself to that of dozens of artists and writers across the decades, nothing yet produced has crossed that line. Lum and Ataru remain in relationship limbo. Necessarily so, in fact, because if it were ever to go further down this route, it would push Urusei Yatsura into being a romance, or at least a romantic comedy, and that would be unsuitable. The joy of Urusei Yatsura is its essential lack of genre.

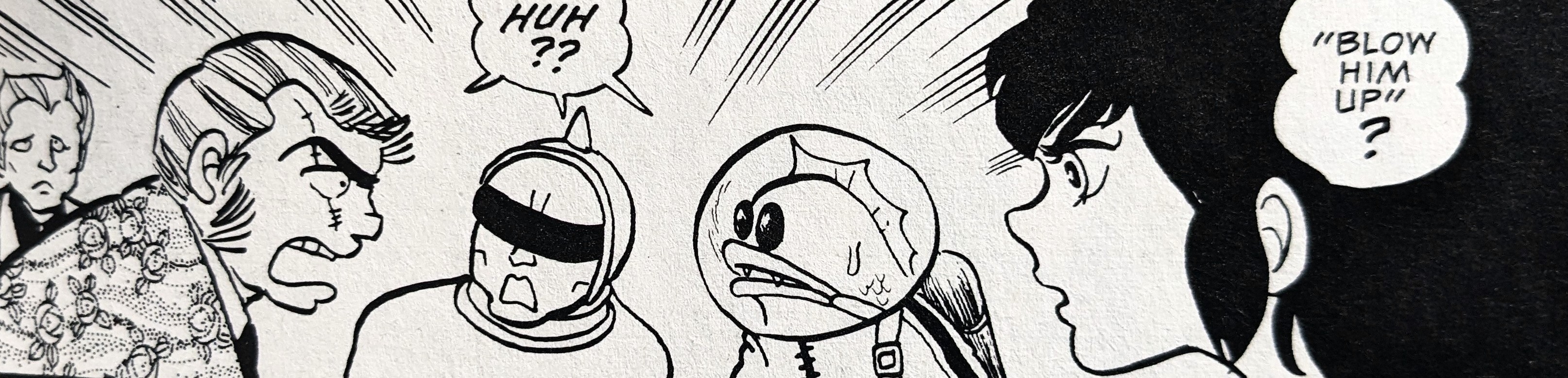

One can of course never be sure what the young Takahashi was going for when she began Urusei Yatsura, her first major serialised manga. It appears she was doing a bit of a dry run with Katte no Yatsura (same problem with translation here – most of the time it becomes ‘Those Selfish Aliens’), a weird little one-shot featuring aliens infringing on the life of a semi-normal Japanese paperboy, a race of malevolent fish people, and a liberal sprinkling of very Japan-specific cultural references. Happily, it was translated and published by Viz Media back in the olden days so it is technically available, alongside most of the rest of Takahashi’s work. It doesn’t appear that this story has seen the light of day recently as part of the new Viz collected editions from the wider Rumic universe as have Mermaid Saga and Maison Ikkoku (and neither has my personal favourite, Maris the Chojo (ザ・超女, ‘The Supergal’)), but hopefully it will find its way into an anthology in future.

So in a similar fashion to Katte no Yatsura, Urusei Yatsura (henceforth UY) resists both translation and categorisation. Takahashi’s later work tended toward recognisable genres; Maison Ikkoku (a slice-of-life romance with comedic elements), Ranma 1/2 (a martial arts comedy with romantic elements) and Inuyasha (a shōnen-style fantasy romance) all sit fairly comfortably in Big Comic Spirits. UY in contrast became a well from which Takahashi could pull pretty much any idea and play around with it, so that a manga that begins as a ridiculous alien-human love triangle can also be about an incompetent girl gang from space attempting to establish itself over what they perceive as their predecessors/rivals, or Dracula, or a disco-dancing warlock. During its serialization in Weekly Shōnen Sunday and to an even more ridiculous extent in the original anime run and accompanying features/OVAs, UY was essentially whatever people wanted it to be. Mamoru Oshii may have stuck to the source material fairly strictly for most of the original TV run and the first feature-length, Only You, but with his second go at directing he stretched and squeezed the familiar characters and settings of Tomibiki into the sort of dialogue-heavy cerebral mystery he would later explore in Ghost in the Shell, and even more so in its sequel. I’m still not sure exactly what Kazuo Yamazaki was going for with Lum the Forever but that bizarre outing, so nearly an interesting mess, serves as further evidence that UY is basically what you make it, whether you are the creator or the audience. To some it really is a romance first, everything else second. To others it is screwball comedy. I’ve been reading/watching UY for a long time, and lately I’ve been thinking about why I love it so much. What makes this weird piece of oddball showa history special?

urusei yatsura and me

I won’t go into my own journey into anime/manga fandom too much here, because I would like to talk about that quite a bit and this isn’t the right place. Instead I will touch on how I came across UY and Takahashi’s other works.

Within the late 90s/early 2000s nerd sphere, there was a considerable undercurrent of enthusiastic anime fans. I had been fascinated with anime as a medium since I had first seen adverts for ADV and Viz Media VHS releases in the games press (Computer and Video Games particularly) and nerd-adjacent publications such as 2000AD. Curiously, UY never really featured in this ads, as far as I can remember. It did, however, come up very quickly as I delved further into this world. I bought a couple of foundation texts: Manga! Manga! The World of Japanese Comics by Frederik L. Schodt, and The Anime Encyclopedia by Jonathan Clements and Helen McCarthy. The latter is fairly self-explanatory, but the former is a fabulous short history of Japanese sequential art, complete with a lovely collection of excerpts from selected seminal works, such as Tezuka’s Phoenix and Riyoko Ikeda’s Rose of Versailles. Since it was published in 1983, one might forgive the book’s failure to mention any of Takahashi’s works to that point – UY had made its debut five years prior, Maison Ikkoku three – but it remains an undisputed classic in a very limited area of study. To me it was something of an eye-opener: this (that is, manga/anime) was not something that was limited to a few intriguing titles in the back pages of a magazine, but an entire medium, a new realm in which things were done a little differently.

Still, it was very unusual to encounter UY in the wild. There existed a sort of canon of available works at that point (the late 90s), with the landscape dominated by successful imports like Akira, Ghost in the Shell, Neon Genesis Evangelion, Slayers, Record of Lodoss War, The Vision of Escaflowne, the almost-mainstream Ghibli features, and even oddball distributor gambles like Agent Aika or the early Masamune Shirow OVA Black Magic M-66. UY, whose anime would have been 18 years old in 1999, was considered vintage even then. The most recent installment of the series had been the final feature-length, Always My Darling (いつだってマイ・ダーリン), which was and is widely considered to be the absolute worst thing to happen to the series in its history. The mid-to-late 90s anime enthusiasts were concerned with other things, I suppose: I certainly was. I really had no sight of the Rumic World until I picked up Comics, Comix and Graphic Novels: A History of Comic Art by English pop culture historian Roger Sabin. Being a broad overview of comics in general and focussed more expressly on underground and indie comics of the West, its profile of manga was fairly light, but it did mention among other things, a weird martial arts comedy called Ranma 1/2 and Urusei Yatsura. I immediately loved the art style – comic and exaggerated but with a lovely rounded feel to the characters – but that was it. I couldn’t find anything like that in my local bookshops or libraries, so I moved on.

The beginning of the 21st century coincided with the rise of fast home internet access, which transformed anime fan culture from a cluster of Usenet boards and forums into a network able to distribute full(!) episodes of fan-translated anime, not to mention high-resolution scanlations of even very recent manga releases. Titles like Azumanga Daioh, The Melancholy of Haruhi Suzumiya and Rozen Maiden made an enormous impact on overseas anime fan culture between 2000 and 2010 because they were available (legally or not) to and to some extent marketed toward internet-savvy young people. Alongside these early megahits, however, was an increasing potential for old-school anime fans to preserve and revive older titles. Thanks in part to the obsessive nature of Japanese fans, laserdisc and DVD rips of thousands of titles were quickly available to torrent. Just as early peer-to-peer systems Napster and Limewire (Bearshare?) had done for music discovery, torrenting did for anime (and a lot of other stuff). Curious about that series that had really cool cover art on its laserdisc release? Well, look it up on a respectable torrent indexing site and you, too, can enjoy Doomed Megalopolis! A good portion of anime’s rich history had become wonderfully accessible, and so it was that I was able to enjoy a low-definition .avi of the first episode of Urusei Yatsura.

lum the notorious

At no point does Lum claim to be “notorious”, and that is only one of the mystifying elements of this bizarre debut double episode. Without some prep, not much makes sense. Broken into two segments (as were most episodes in the first 22 episode “season), this is a simple adaptation of the first manga chapter. We are introduced to Ataru Moroboshi, whose two character traits are being an obsessive and ineffective girl-botherer and being catastrophically unlucky. The latter is confirmed by an unappealing Buddhist monk named Cherry whose real name is Sakuranbo (錯乱坊) but who prefers the English word due to the kanji having several unpleasant connotations. Ataru is apparently in a fragile relationship with a fellow Tomobiki High School student Shinobu Miyake. She is prim, proper, and freakishly strong, though that is only revealed later.

Leave a comment